2006/10/17

The New Digital Divide: a Generation Gap

According to the report, the 16-34 age group leads the way for Internet socializing.

This is the present generation gap, and online marketers must figure out new ways to bridge the gap or risk seeing revenues decline.

Social networking sites are an influential platform that more advertisers must take advantage of. According to the report, “Although are not yet bypassing regular media sources in favor of creating, sharing and consuming user generated content, there are significant implications for the advertising industry for future trends.”

Also visible, a growing interest for streaming content, whether TV shows, radio programming or new music. Advertisers will use this platform by creating video, audio and text-based streams to be distributed online. For them, the greatest challenge and potential revenue boost is to integrate the web technology within a broader communications context.

Small is beautiful for Web 2.0 Start-ups

Again, Small is Beautiful for Web 2.0 Start-ups.

More software start-ups are launching with relatively small upfront investments and niche products delivered via the Web.

Some investors and entrepreneurs contend the traditional model of starting companies--multi-million dollar VC investments, long product development cycles, and big price tags--is waning.

2006/10/16

Is Second Life a Web 3.0?

A contribution from Luis Moniz (Thanks!).

Related with post "What is Web 2.0"

Is Second Life a web 3.0?

I heard a few months ago someone talked about "the amazing world of second life".

Is it a game? a virtual world? a real world with virtual players? I still haven't found what is it... until I read that is been used my marketers to research and test new products and services.

A huge focus group with 902.643 residents!!...

In October issue, Wired published “Let's Go: Second Life - Taking a trip to the coolest destination on the Web?”. Online edition is now available.

What is Second Life?

Second Life is a 3-D virtual world entirely built and owned by its residents. Since opening to the public in 2003, it has grown explosively and today is inhabited by 900,000 people from around the globe.

From the moment you enter the World you'll discover a vast digital continent, teeming with people, entertainment, experiences and opportunity. Once you've explored a bit, perhaps you'll find a perfect parcel of land to build your house or business.

You'll also be surrounded by the Creations of your fellow residents. Because residents retain the rights to their digital creations, they can buy, sell and trade with other residents.

The Marketplace currently supports millions of US dollars in monthly transactions. This commerce is handled with the in-world currency, the Linden dollar, which can be converted to US dollars at several thriving online currency exchanges.

2006/10/12

Netrospective: 10 years, 100 moments of the Web

Google agrees to buy YouTube

International Herald Tribune, Bloomberg News, October 9, 2006

International Herald Tribune, Bloomberg News, October 9, 2006Google, the most-used Internet search engine, agreed to buy YouTube for $1.65 billion, adding the largest video-sharing site on the Web and an audience that watches more than 100 million clips a day.

2006/10/11

What Is Web 2.0

Design patterns and business models for the next generation of the web software, as seen by Tim O'Reilly.

A Brief History of the Internet

Read this Brief [but accurate] History of the Internet and other Internet histories, at the Internet Society Organization website.

"Digital 2.0: Powering a Creative Economy"

Listen to the World Economic Forum discussion panel "Digital 2.0: Powering a Creative Economy", with John T. Chambers (Cisco), Bill Gates (Microsoft), Eric Schmidt (Google), and Niklas Zennström (Skype).

When the discussion warms up, there are some interesting insights into changing business models in a digital world.

eMarketer's Seven Predictions for 2006

JANUARY 11, 2006

January is here again and with it comes the usual slew of projections and forecasts for the coming year. Not to be left out, eMarketer joins the fray.

Here's what to look for in 2006:

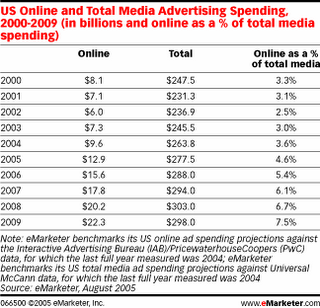

1. Online Advertising Passes the 5% Mark

5.4% of all US advertising spending will be devoted to the online channel in 2006. This is the first time the figure has exceeded 5%. The Internet's share of advertising spending will be greater than that of the yellow pages. In fact, some of the money going online comes from the yellow pages, as certain Web sites replicate its functions.

By 2009, despite a fall in total ad spending, Internet ad spending will rise to over $22 billion. This will represent 7.5% of all advertising spending, and be greater than radio's 7.3% share of the market in 2005.

2. Retail E-Commerce Grows (Even More)

US online retail sales will grow from $87 billion in 2005 to $105 billion in 2006, a healthy 21% increase. More spending by affluent baby boomers and the rising buying power of Web-savvy young consumers, coupled with the spread of high speed broadband Internet access, are the key factors that will drive retail e-commerce sales to new heights.

3. Broadband Continues to Spread

The US broadband market reached an important inflection point in late 2004 and early 2005 when the number of broadband Internet users overtook dial-up users for the first time. eMarketer estimates that there are now over 105 million broadband users in the US. This will rise to over 124 million in 2006 and will exceed 157 million in 2008.

Rising broadband penetration is contributing to e-commerce growth, helping transform the Web into a truly multimedia environment and making new Internet services such as VoIP telephony a reality. The implications and opportunities for online advertising and marketing are extensive.

4. Online Video Thrives

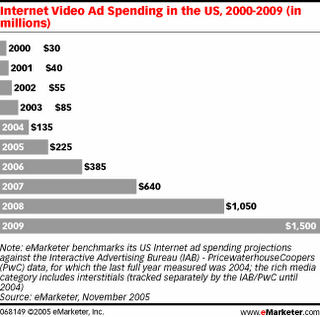

Online video distribution and consumption will grow significantly in 2006. The Internet is increasingly seen by consumers as an entertainment platform, helped by increased broadband penetration and the adoption of improved digital rights management (DRM) technologies by content providers. The trend is also reinforced by supply-side moves such as increasingly sophisticated video search services from Google and Yahoo! and Apple's drive to distribute video content through iTunes.

Opportunities for video-based online advertising will rise on the back of this trend. US spending on Internet video advertising will increase by a stunning 71% in 2006, to reach $385 million. 2007 is likely to see similar growth.

5. Video on Phones Comes to Life

The rise of the very small screen will start in 2006. It is difficult to gauge exactly how many mobile TV subscribers there are, since none of the wireless operators is sharing numbers. But based on the data that is available, eMarketer estimates that in 2005 there were 1.2 million US consumers who watched TV programming on their mobile phone (either live programs or pre-recorded video). This number will more than double in 2006 to 3 million phone users. By 2009, there will be 15 million phone video viewers, an estimated 6.2% of total mobile phone subscribers.

6. Search Engine Portals Expand Their Reach (Even Further)

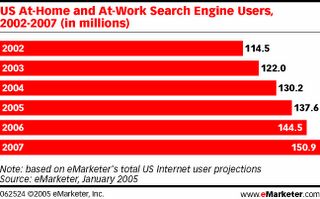

About one half of all US Internet users visit Yahoo! every month. Globally, the "Big Four" portals (Yahoo!, Google, MSN and AOL) have an audience of close to 30% of all the world's Internet users. These astounding figures will not diminish in 2006. Content-hungry, broadband-connected Internet users will turn to these portals in increasing numbers.

At the same time, locked in competition over audience size, the search engine providers will deliver more — and increasingly powerful — ad-supported web applications. They will also enhance and push their local search capabilities. These efforts will help drive the total number of US search engine users up from 138 million in 2005 to 146 million in 2006. This 5% increase will be more than double the increase seen in the total number of US Internet users.

7. IP Telephony Enters the Mainstream

By 2006, a substantial migration to VoIP services will be underway in the US. The number of VoIP access lines will grow from an estimated 10 million in 2005 to just under 14.5 million in 2006. A significant transformation of the telecommunications industry is inevitable. Cable providers and established telecoms companies will go head-to-head in the battle for residential and business VoIP subscribers. eMarketer expects the cable operators to win market share at the expense of the telcos' traditional phone businesses.

Newcomers include dedicated VoIP providers such as Vonage and Skype, as well as the major search engines (AOL, MSN, Yahoo! and Google), who offer low-grade telephony via their instant messaging platforms. However, all of these still require that end-users have broadband Internet access, virtually all of which is supplied by the cable companies and telcos.

©2006 eMarketer Inc. All rights reserved

Definitions from “Encyclopedia of the New Economy”

Authored by Wired and Anderson Consulting/Accenture

Attention economy A marketplace based on the idea that while information is essentially infinite, demand for it is limited by the waking hours in a human day.

Attention economics has been around for at least as long as there have been commercial media, whose true products are not sitcoms (or magazines), but eyeballs for advertisers. Interactive media take this concept a step further: they allow attention - say, a Web site's traffic - to be bought, sold, or bartered and instantly shipped to other sites anywhere in the world. And the whole business can be scaled up to a billion people watching the Olympics or down to a custom-tailored audience of you.

Attention economics helps explain some of the Net's seeming commercial anomalies, including the explosive growth of high-visibility navigation sites like Yahoo and the proliferation of free (to the user) products and services. Another example is the skyrocketing value of bankable sports, film, and TV stars who can catch eyes amid the fray. In an ever more trafficked world, tools for getting (and keeping) attention will be increasingly valuable.

Bandwidth A network's carrying capacity, rarely sufficient.

The term bandwidth used to mean the size of the slice of the radio spectrum available for a transmission. Today it is mostly used to describe the rate at which information - measured in bits of data per second - can move between computers. As such, bandwidth determines a network's ability to deliver information goods and services. But that also makes it one of the new economy's key limiting factors - ask a Web surfer stuck with a 28.8-Kbps modem, or consider MTV pondering (in the near term, anyway) online music videos.

Fiber-optic cable - currently being laid as fast as backhoes can dig trenches - and the late arrival of TV's deep-pocketed cavalry are changing that. Pundit George Gilder has proposed a bandwidth corollary of Moore's Law: Backbone capacity will triple annually for the next quarter century. It could happen. Already, corporate Internet users are measuring their access in gigabits per second - sufficient to start realizing the trillion-dollar pipe dream of TV and Internet convergence. Meanwhile, the $2 billion, Denver-based telco Qwest is building from scratch a new US network with a top capacity of 2 terabits (2 trillion bits) per second - sufficient to transmit the entire contents of the Library of Congress cross-country in 20 seconds.

The astonishing economies of fiber-optics have revived - more quietly, this time - a version of the nuclear-power industry's old slogan: bandwidth could someday be "too cheap to meter." But for homes in particular, despite talk of wireless solutions, there remains the "last mile" problem of pulling fiber to individual customers. And then there is a question that the old economy answered by forcing regulated phone monopolies to provide universal service: Should everyone go to bandwidth heaven together?

Churn Customer disloyalty.

Ever faster innovation means more possibilities for customers to decide they don't really like your product after all - or to realize that someone else has a cheaper, faster, or better version. And the new economy's ever more efficient markets make it less costly - in money, time, or both - for consumers to make the move.

AOL learned all about churn when it developed a busy-signal problem late in 1996 and tens of thousands of expensively acquired customers bolted to less-popular rivals. Long distance phone services and credit card companies encourage defectors by spewing millions of pieces of junk mail - and, more recently, Internet banner ads - offering everything from reduced rates and frequent-flier miles to cash.

Internet retailing looks to be churn's next great frontier. Ecommerce pioneers are responding with new ways to build customer loyalty - personalized service, for example. But aggregators like Yahoo and Excite make it pathetically easy to click from one e-shop to another - even as location, store layout, and other traditional tools for building competitive advantage vanish.

Commoditization The process by which the complex and the difficult become simple and easy - so simple and easy that anybody can do them, and does.

Commoditization is a natural outcome of competition and technological advance: people learn better ways to make things and how to do so cheaper and faster. Prices plunge and essential differences vanish - look at cheap PCs or mass-market consumer electronics.

The new economy puts commoditization into overdrive, speeding the flows of information, component parts, and finished products to the point where products can progress from idea to commodity seemingly overnight. The only real antidotes are barriers to entry - say, a niche market too small to attract big competition. Or innovation sufficiently rapid to stay ahead of the pack. Or - if technology itself doesn't conspire to undermine it - an old-fashioned monopoly.

Convergence Bits are bits.

It's the quintessential new economy idea: translate everything, from Seinfeld to your kid's homework, into the digitized 1s and 0s of computer language, then make it all available anywhere in the world via the Net. Big dollars are already being wagered on the prospect of TV and PC convergence - the idea that the two most powerful devices of the late 20th century can be merged into a single seamless information system. (Oh, and throw in the telephone, too.) It is a mesmerizing vision with profound ramifications for the corporate media landscape of the not-too-distant future. Stay tuned.

Coopetition Cooperation between competitors.

Altruism doesn't have to be the opposite of self-interest. Sometimes - when trying to create a new market or hedge the risks of an expensive innovation - it can be a way to get what you want.

Coopetition - alliance, in the case of noncompetitors - is especially common in the computer industry, where consumers want to know in advance that a broad range of companies will support a given technology. Companies cooperating helps such markets grow faster, without requiring prolonged periods to shake out competing technologies. It also helps focus scarce resources - though not necessarily on what is ultimately the best technology.

Coopetition often involves companies agreeing not to battle in one market even as they fight like dogs in others: witness the current "grand alliance" of Sun, IBM, Apple, and Netscape, which is supporting the open programming language Java to undermine Microsoft's market power. More commonly, companies will compete on actual products even as they cooperate on technical standards, sacrificing a degree of independence to increase the odds of success for the technology as a whole. Look at the huge success of American Airlines in opening its Sabre reservation system to competing carriers.

Needless to say, coopetition makes antitrust authorities nervous. There is an old-fashioned word for competitors who agree not to compete - cartel, with its overtures of price fixing. Today's regulators appreciate the theoretical advantages of coopetition, but in practice they still want to be sure that they can distinguish it from old-fashioned collusion. And as Microsoft's on-again, off-again antitrust investigation shows, separating new ways of doing things right from old ways of doing things wrong is far from easy.

Cycle time How long it takes to bring a new product to market or to upgrade an existing one.

Prior to the industrial revolution, cycle times could often be measured in centuries. They've been declining ever since, pulled along by ever larger and ever hungrier markets and pushed by increasingly supple technology. Detroit automakers could stretch a basic model change over a decade; competition from the swifter Japanese changed that. Today exhausted Web developers talk about "Internet time," where the cycle time gets close to zero - essentially, nonstop continuous change and innovation.

Data mining Extracting knowledge from information.

The combination of fast computers, cheap storage, and better communication makes it easier by the day to tease useful information out of everything from supermarket buying patterns to credit histories. For clever marketeers, that knowledge can be worth as much as the stuff real miners dig from the ground.

More than 95 percent of US companies now use some form of data mining - often nothing more than mailing lists, but increasingly the more sophisticated psychographic profiles of potential customers that make privacy advocates shake. It's a perfect hot-button political issue: Whose data is it, anyway?

Disintermediation Cutting out the middleman.

As networks connect everybody to everybody else, they increase the opportunities for shortcuts. When you can connect straight from your desktop to the computer of your broker or bank, stockbrokers and bank tellers start to look like overpriced terminal devices.

Disintermediation first gained momentum in financial markets when customers began forsaking savings banks for their stockbrokers' money market accounts - denying banks the opportunity to make a nice return by investing the funds in money markets themselves. Now entire swaths of the economy are vulnerable: stockbrokers, real estate agents, anybody who picks up a phone for a living. And maybe generic clothing stores, computer resellers, and record shops, too - thanks in part to the cheap, convenient, and increasingly universal distribution networks otherwise known as FedEx and UPS.

In practice, though, disintermediation more often means changing jobs, not eliminating them. And, in the process, it can create opportunities for new and different middlemen - look at online bookseller Amazon.com and stealth retailers like CUC International. As networks turn increasingly mass-market, everyone involved in sales is playing a duck-and-weave game of disintermediation and reintermediation. To the winner go the customer relationships.

Education The ability to train yourself.

Training - acquiring the skills necessary to do a specific job - is the most important form of investment in an information economy. Education allows people to manage their own ability to acquire and use knowledge - and, thus, to manage their own careers and lives.

More and more people are grasping that opportunity. Today nearly half of all US college students are over age 25, returning to school to increase their knowledge. Many mature students are financed by their employers. More still are investing in themselves, which is a double-edged sword for bosses: Better-educated employees are good for business, but they also transform bosses from employers into clients.

Friction-free What markets want to be.

One of the obvious effects of information technology is to make transactions of all kinds smoother. Indeed, the hefty profit to be wrung from eliminating high transportation costs, poor communications, and parasitic intermediaries are a driving force behind the whole new economy.

Friction-free economics means empowered consumers, accelerated market development, and shorter life spans for products and jobs. No one's roped into anything anymore. Efficiency rises, costs fall, and basic rules are rewritten - hypercompetition prevails, and the victors win by adapting quickest to change. Here lies an interesting dilemma: When it's harder and harder to keep a grip, how do you sustain competitive advantage?

Information food chain Data, information, knowledge.

All bits are not created equal. Some carry useful data, others are random marks on a page, garbage on a disk. Digested by the human mind, data becomes information - messages that change the way we think about the world. Knowledge is a step further: mental tools that make sense of things, an evolving set of beliefs about the world.

Once the world's information truly is at everybody's fingertips, the only thing that will distinguish the rich and powerful from the merely struggling is what's in their heads - the knowledge of what information to call for and how to put it to work. Knowledge is what makes mere information valuable. Which is why management guru Peter Drucker famously calls it "the only meaningful resource today."

Innovation The only source of sustainable growth.

Constant innovation has long been recognized as vital to healthy economies, somewhat less so for individual companies, whose success has often depended on making one great innovation and then milking it.

The rapid spread of information technology has shifted the nature of competitive advantage. Owning a vault full of patents or a high-efficiency production line is no guarantee of anything. Some firms, as MIT's Eric von Hippel points out, get their new ideas from their customers; others look to their suppliers for the lead. Either way, the key is to "own" a problem that needs solving - to have an understanding of the world or a relationship with customers. To keep up, you need the right answers; to get ahead, you need the right questions

Intellectual property Legally protected ideas.

Intellectual property - patents, copyrights, and trademarks - is an intangible asset that can be bought and sold. The laws that govern it try to balance competing interests: innovators, who typically want more control over their ideas and to profit from them, and everybody else, who typically want looser controls, so that other innovators can use them to move things even further ahead. The result is a set of deliberately leaky laws.

Digital technology's easy creativity has set off a vigorous debate. Some key intellectual-property players - notably, Hollywood movie studios - say that the laws should be tightened to compensate for the Net's loose environment. Opponents say the laws should, if anything, be eased to prevent existing owners from profiteering as the Net multiplies their markets.

Another hot issue is databases. US law generally doesn't protect collections of facts: Companies can - and do - strip information from telephone books and other freely available sources, then sell the reconfigured results as they like. The original owners argue that they would produce even more if they could get more - airtight rights. But most suggestions on how to offer greater protection would put a damper on everything from scientific research to sports reporting (because teams or leagues might assert ownership over players' stats).

Some digital enthusiasts argue that the very term intellectual property is an oxymoron. They are probably right. But that doesn't make the laws governing it any less important - or any easier to write.

Intellectual capital The sum of what you know.

The most valuable part of any company is what walks in and out of its doors every day. The working knowledge that people carry in their heads - knowledge of products, customers, how to work together, and so on - are a company's intellectual capital.

Purists will argue about whether it should strictly be called capital. People, after all, cannot be bought and sold like most traditional forms of capital. But the bottom line is that having the right team is more crucial than ever. And now that expertise can be translated directly into investment cash, it is a lot more like old-fashioned capital than purists may realize.

Just-in-time learning Knowledge at your fingertips.

Just-in-time education does for knowledge what just-in-time delivery does for manufacturing: It delivers the right tools and parts when people need them. Instead of spending months in boring classrooms, people can use networks and clever databases to answer questions and solve problems as they crop up.

Efficiency isn't the only issue: Technology's breakneck pace makes it ever harder for training to keep up. Just-in-time education means constantly upgrading your work force's knowledge base, supplementing - or even replacing - traditional technical schools and four-year colleges. Not as much fun as dorm life, though.

Knowledge management Husbandry for ideas.

If knowledge is the only real asset, why not manage it like any other? That thought has spawned a mini-industry, from purportedly knowledge-capturing software to corporate "chief knowledge officers" responsible for making their companies smarter. A lot of these efforts are misguided.

The problem is that knowledge isn't like other inventory - it can't just sit in the warehouse until needed, then be dusted off and used. It has to be kept fresh, relevant, and alive. It has to be exercised through continual discussion and revision. And it cannot be managed separately from the people in whose heads it resides. That's the reason companies that successfully manage their knowledge focus on putting people in touch not with vast databases, but with other people. Typically, this means putting questions on an equal footing with answers, because it forces those with knowledge to reshape it continually, to fit their colleagues' needs. In the process they continually renew their knowledge and avoid seeing it depreciate into irrelevance.

Lock-in The high cost of switching technological horses.

Hardware and software are the least of what companies invest in information technology. The really important investments are data and the time and effort spent learning how to use new systems. Protecting those investments explains why many companies stick with obsolete, inefficient computer systems. The cost of converting to new technologies and retraining workers outweighs the benefits - or seems to. That extra cost, multiplied by thousands of companies and millions of users, is called lock-in. Or Windows 98.

Lock-in can happen with many kinds of standardized products - railroad gauges and VHS video are classic examples. Information technology is especially vulnerable because it typically involves integrated systems, in which it is hard to change only a few things.

Big hardware and software firms tend to like lock-in: It keeps competitors at bay. But in order to keep customers locked in, companies have to waste time and effort tending old technologies, even the best of which eventually run out of steam.

Mass customization The market of you.

The Industrial Age created a dilemma. Goods could be mass produced, standardized, and cheap. Or they could be individually made, unique, and expensive. The information age - and the advent of computer-controlled machine tools - lets consumers have it both ways: customized and cheap, automated and personal. So the question isn't whether people can choose - it's whether they'll want to.

Off-the-rack suits and off-the-showroom-floor cars relieve you of having to think in too much detail about what you want. Custom-fit Levis? Fair enough. Custom-configured computers? OK. But for most people, utter freedom of choice can lose its appeal pretty quickly, no matter how low the price. Custom-created audio CDs, to take one current fad, make sense only if you already know, song by song, exactly what you like.

Still, mass customization will feed what has been termed the deindustrialization of consumer-driven economics: increasing status for things that can't be supplied on a large-scale basis, period. Montana ranches, Ming vases, and massages, for starters.

Moore's Law High tech's tidal force.

In a 1965 speech, Intel chair (now emeritus) Gordon Moore made a famous observation: With price kept constant, the processing power of microchips doubles every 18 months. Moore's Law, as it came to be known, governs Silicon Valley's most important product cycles, for hardware and software alike. And its relentless drive has spawned whole new industries: digital watches, calculators, videogames, the Internet - with smart phones, digital TV, and who knows what else on the horizon.

How long will Moore's Law hold up? Or put another way, when will its hockey-stick growth curve droop into a more mundane S? Twenty years is the usual guess, which is another way of saying no one knows.

Narrowcasting More signal, less noise.

Electronic media let you pick your weapon. Broadcast is for brand building in mass markets. Interactivity ferrets out individuals. And between them lies narrowcasting, the perfect tool for mining niche markets.

Narrowcasting's pioneer days were on cable television, but its true home will be the long-anticipated convergence of TV and the Net. Web-based streaming-media technologies already make possible live telecasts to audiences as large as 50,000 people at a cost per viewer lower than cable. When you're paying to reach people, it pays to reach only the ones you really want.

Netheads versus Bellheads The great telecom divide.

Anything the phone system can do, the Internet can do better, and cheaper - or soon will. The International Telecommunication Union, a Geneva-based Bellhead redoubt, admits that transmitting data over traditional phone networks already costs four times more than sending it by Internet packet switching. That difference is widening. And some of those cheap data packets are already carrying digitized voices, taking bites out of the telcos' core business. No wonder even AT&T and Deutsche Telekom are investing in Internet telephony.

But more is at stake. Netheads and Bellheads have fundamentally different styles of business. Bellheads "serve" customers; Netheads want to enable customers to serve themselves. Traffic on the Net is doubling every six months; voice traffic is growing at less than 10 percent each year. The only real question is why the Bellheads don't get smarter faster. One answer: massive sunk costs.

Network externalities Connections count.

Fax machines and board games share an economic quirk: each new one sold - or, in the case of games, each new enthusiast who learns the rules - adds to the value of the rest. A fax machine isn't worth much if there are no others to communicate with; board games aren't much fun if no one else knows how to play. Thus the whole adds to the value of each of its parts.

Network externalities - a term for the effect one person's decision to buy into a network has on others who are still thinking of buying in - have been the Net's rocket fuel: the more people who connect, the more valuable a connection becomes. But the Internet in turn is bringing network externalities to the economy as a whole. Knowledge is affected by the same sorts of network externalities as Internet connections themselves; having the equipment to receive messages is no more important than having the knowledge to understand them. This explains why the future seems to happen so fast on the Internet. Change accelerates itself. And yesterday's arcane knowledge becomes today's essential information.

New media Communications for all, by all.

Old media divides the world into producers and consumers: we're either authors or readers, broadcasters or viewers, entertainers or audiences. One-to-many communications, in the jargon. New media, by contrast, gives everybody a chance to speak as well as listen. Many speak to many - and the many speak back.

That doesn't mean tomorrow's prime-time television will consist of home videos and talk shows beamed live from the neighbors' living room. Talent - and marketing muscle - matters, and there will always be hit shows and stars. Television and other old media are not going to vanish, and neither will their proprietors. But they will face new competitors and transformed markets.

New media enables even the smallest, most scattered electronic communities to share - or sell - what they know, like, and do. What broadcasting atomized, new media brings back together.

Privacy Vanishing species.

Industrialism and privacy go hand in hand. Traditional mass-production companies had little reason to learn much about individual customers, because they couldn't do anything with the knowledge anyway. Mass-customization creates a new dilemma: fear of companies knowing too much.

The problem is that the act of gathering information about customers makes some of those customers very nervous indeed. The (not unreasonable) worry is information gathered ostensibly to serve you better might someday be used against you. Or sold to someone with ill intentions.

Governments have already begun trying to regulate privacy - futilely. Over the long term, honesty and transparency are the best cures. Tell people what information you are gathering, and why. Explain to new prospects how you got their name. Be careful with whom you share customer information. Don't gossip.

And we'll all have to get used to the fact that there will simply be less privacy. Technology is creating a global village, and villages are not particularly private places. The healthy ones thrive instead on respect.

Supply chain Virtual production lines.

As companies look outward for more and more of the components of what they make or do, being a good shopper has become a key to competitive advantage. That means knowing when to keep suppliers at arm's length - in order to maintain the freedom to shop elsewhere - and when to forge close relationships, to innovate together. It also means a new power struggle, as supplier and customer tussle over who should do what.

Wal-Mart, for example, uses its Retail Link network to give suppliers instant feedback about how their products are doing - what's in stock, what's moving, how competing goods have sold, and so on. In return, Wal-Mart expects the suppliers to tailor deliveries and promotions to meet Wal-Mart's needs. Wal-Mart warehouses less inventory - in some cases none at all - and still keeps its shelves stocked with what's hot.

Mass-market computer makers like Dell and Compaq are raising efficient supply chain-building to a high art. Tying your corporate destiny to other companies - particularly companies that might someday decide to become competitors - does not always make for restful nights. But it works for customers - and it beats being run out of business by other companies more willing to take risks for the customer's benefit.

Transparency What you know won't hurt you.

Free-flowing information - transparency, in the jargon - is the key to efficient markets (not to mention good government). Look no further than Asia's erstwhile "tigers," whose multibillion-dollar national banking systems choked on their own smoke and mirrors. Transparency builds confidence; secrecy builds fear. Hence one of the IMF's main bailout conditions for the wounded Asian economies: real financial reporting, at all levels.

Even for individual businesses, secrecy may not be all it's cracked up to be. With the spread of the Internet, more and more companies are realizing that the benefits of swapping information - with customers, suppliers, even competitors - can often outweigh the costs. Employers still fret about their companies' most valuable knowledge walking out the door each night. But the new economy - from Microsoft enlisting its customers as bug-fixers to Wal-Mart putting its whole supply chain online - raises another possibility: the more you share with the rest of the world, the faster everyone learns.

Trust Social capital.

As historian Francis Fukuyama has pointed out, the free-wheeling, ad hoc organizations of the new economy can exist only if their members are willing to trust each other. Which may be why the new economy is growing fastest in relatively new societies like the US - which have a tradition of getting along with strangers - and still struggling in more suspicious and traditional ones (France, Germany, and Japan). The good news, though, is that the Net helps to create its own social capital. Once someone you've never heard of has replied to your email request for information, you just might feel inspired to reply to some other stranger. And from small acts of faith, mighty economies grow.

Ubiquity Be there now.

Networks put everybody constantly in touch with everybody else. And that means you can sell anything anywhere to anyone, at any time. No need to get Joe Customer into the store - you can sell to him wherever he is, as soon as the impulse strikes him. In a networked economy, success goes to those who can insinuate themselves into that moment, when unarticulated desire - the urge, say, to buy a book or trade some shares - becomes real demand for a specific thing. And think of all the rent you're saving.

To Do: "Blogging for Dollars"

Read "Blogging for Dollars" and answer these questions:

1. Who is Micheal Arrington and how is he making $60K/month?

2. What is Fark.com?

3. Why are some people and businesses able to make money blogging?

4. How are Banana Republic and Coca-Cola using blogs according to the article?

5. How big is the current market for blog ads?

6. Who is John Battelle and what has he done for the blogging world?